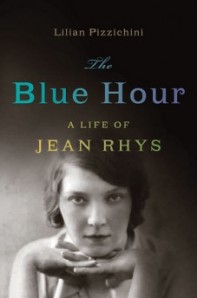

Some thoughts on Jean Rhys- her personality, times and the biography ‘The Blue Hour- A Portrait of Jean Rhys’ by Lillian Pizzichini, Bloomsbury, 2009.

Dealing with the life of anarchic writer Jean Rhys could not have been easy- how should one approach a life of such rebellion and not sound judgemental- how to face such torment without being patronising or wallowing in it. I found Pizzichini’s treatment of Rhys in The Blue Hour to be fair- if not slightly light. This book is a breeze to read and is not heavy and laborious in it’s detail- giving enough to maintain momentum, culling anything unnecessary or unavailable. I liked, furthermore the tone of this book- no judgement here , the reader is encouraged to sympathise or at least laugh with Rhys even at her most vile. Spanning Rhys’s life from Dominica, through Paris in the 20’s, wartime mainland Europe and London during the blitz, Rhys was blessed or cursed to be born into interesting times. However, she isolated herself, and was seemingly and believably just not able to interact with people in an acceptable way, becoming violently angry with life and humanity as she aged into a difficult drunk before achieving fame in her 70’s around the time when she was producing her masterpiece (and my all-time favourite book) ‘Wide Sargasso Sea’. Her late acclaim was acknowledged by her to be too little too late, and unfortunately, happiness always evaded Rhys.

Part of the ‘problem’ with Rhys seems to have been the inability to sync with the world, to put down roots or empathise with others in such a way that would inspire her to act in a compassionate way. Combined with a huge need to please and be loved, Rhys spent much of her long life in mental torment. This tortured nature was the root of her talent though, and an affinity with misery, and ability to plumb the depths and recesses of the psyche is what spurned her to create her best work which flowed out of her in a cleansing cathartic rage.

Rhys is, we must recognize, someone whose quirks would instantly be forgiven if she had been a man of genius rather than a woman of genius. Refusing to settle, refusing to carry a child, then later refusing to mother for her offspring, refusing to act in a ladylike manner, refusing to appear sane are just some of the ‘transgressions’ which earned her the ‘outsider’ status she internalized for much of her life.

Likened in later life to Johnny Rotten, Rhys comes across as having been incapable of suppressing the urges most people safely keep under wraps at all times. There are some hilarious descriptions throughout this colourful book of her escapades, including chasing a disabled child around a village, attacking her neighbours, clubbing in her 70’s in a pink wig, urinating on an eminent journalist, attacking a fence and publicly wisecracking about Hitler during the second world war. Some sequences are harder to take, including Rhys’s reluctance to bond with her son who subsequently died of pneumonia aged three weeks and Rhys verbally abusing and beating her elderly spouse who was lying in bed after suffering a stroke.

Although her work, especially Wide Sargasso Sea has been appropriated by the feminist cause by literary theorists, Rhys absolutely did not sympathise with feminists. Women were only sympathetic to her when they were vulnerable. She was a ‘man’s woman’ through and through, seeing other women as merely competition, and hopping from one tempestuous affair to the next. To be without a man was annihilation to Rhys, and even if a lover was in prison, the idea of being his partner seemed enough to sustain her. This prizing of sexual love over platonic bonds can be seen on one hand as a manifestation of Rhys’ inability to communicate adequately with others vocally- preferring the immediacy of relationship over the uncertainties of female friendship, preferring written correspondence to talk. She also had a terrible need to be ‘wanted’, and suffered greatly in her old age when her good looks began to dwindle. Her vanity is referred to repeatedly throughout the book, and again these observations say more about a society that expects women to become grey and content as they age, than about a woman who connects sexual desirability with her persona at all ages. Sad to say, I loved the idea of the anarchic 70 year old Rhys cursing and ranting through suburbia in a pink wig, being arrested repeatedly. Rhys was unwillingly part of a dying breed of artists who saw it as their vocation to be wild, bad and mad, instead of the very boring caution of today’s P-C, PR sanitized artists.

This book is well worth a read for anyone looking for a readable biography on Jean Rhys.